Tsurikomi (structure), shinogi et niku

There are many types of blades, at first about of their structure : the size of the different edges, the relating angles ...

The physical composition of the blade (types of steels, composites such as kobuse and so on ...) are therefore not the only variations in structure for a Japanese blade. For example, sometimes you may have heard about shinogi-zukuri blades. This is the most common form today, but it has not been the case always. This article aims to describe the different types of structures. As we know that a lot of athletes will scan this page, we have decided to add a chapter on niku and shinogi widths at the beginning of this article. A chapter which will undoubtedly be of great use if you practice the cut.

The physical composition of the blade (types of steels, composites such as kobuse and so on ...) are therefore not the only variations in structure for a Japanese blade. For example, sometimes you may have heard about shinogi-zukuri blades. This is the most common form today, but it has not been the case always. This article aims to describe the different types of structures. As we know that a lot of athletes will scan this page, we have decided to add a chapter on niku and shinogi widths at the beginning of this article. A chapter which will undoubtedly be of great use if you practice the cut.

Shinogi and niku widths

These two characteristics clearly change the cutting capacity of a blade.

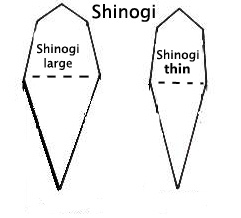

The shinogi is the longitudinal edge close to the mune (back) :

The shinogi is the longitudinal edge close to the mune (back) :

We often speak of broad or thin shinogi, by abuse of language. The incline of the shinogi changes the thickness on shinogi-ji and on the hira-ji (see glossary). Especially, a slightly inclined shinogi (thin shinogi, or Hikushi shinogi, as opposed to the Takashi shinogi) will make the blade more incisive, but less resistant to shocks. A picture is better than a long speech, have a look instead:

Some types of structures, such as the hira zukuri (see below) simply do not have a shinogi. The blade is then very sharp, but it also becomes really weak and not very resistant.

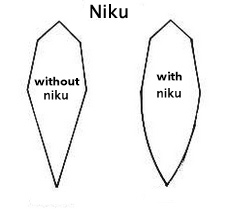

Another element is the niku. Technically, it can be referred to as the curvature of the surface at the level of the hira-ji (see glossary). Again, an illustration will give you a better idea :

Another element is the niku. Technically, it can be referred to as the curvature of the surface at the level of the hira-ji (see glossary). Again, an illustration will give you a better idea :

As you can imagine, the impact on cutting capacity is also very important. A large niku makes the blade very resistant, it was very useful at the time when facing armors. A weak niku produces a thinner edge and therefore the weapon is more aggressive. But an important niku has the advantage of making larger wounds and therefore it was more decisive during fights. Note that technically, we are talking about the sides of a blade (shishi). We distinguish blades with niku by naming the sides "Ari shishi", and without niku as "Nashi shishi". Once again it is by abuse of language that we say "with" or "without" niku. Actually there is always a niku. A flat niku ("without" niku) is called Hira niku kareru. A rounded niku is named Hira niku, and a hollow niku is called Hira niku tsuku.

So, what to choose? But then as today we no longer have to strike again armors, veiling a blade is still possible. As part of a usual practice (bamboo mats for tameshigiri), a katana with a thin shinogi (sometimes called “classic shinogi") and a classic niku (sometimes said "without niku", by abuse of language) is quite suitable. If you are a beginner, it can especially be important to avoid the grooves (bohi) which decrease the thickness of the shinogi-ji and therefore reduce its resistance to shocks. Therefore you can be sure that a classic shinogi and the absence of a niku will improve the quality of your practice.

If we consider outside the sporty point of view, it is to be notified that the presence of a large shinogi or niku are characteristic of forge schools, or periods of the Japanese history. Sizeable shinogis were characteristic of the Yamato style, and of the associated schools (Uda, Mihara, Nio, Kongobei, Naminohira). Some blacksmiths are also known to have forged their blades with large shinogis. The Osafune (mid-Kamakura period), Kozori, and Ichimonji schools generally forged their blades with a thin shinogi. Sizeable niku were very popular during the mid-Kamakura period. These niku have diminished in thickness during the Nanbokucho period.

So, what to choose? But then as today we no longer have to strike again armors, veiling a blade is still possible. As part of a usual practice (bamboo mats for tameshigiri), a katana with a thin shinogi (sometimes called “classic shinogi") and a classic niku (sometimes said "without niku", by abuse of language) is quite suitable. If you are a beginner, it can especially be important to avoid the grooves (bohi) which decrease the thickness of the shinogi-ji and therefore reduce its resistance to shocks. Therefore you can be sure that a classic shinogi and the absence of a niku will improve the quality of your practice.

If we consider outside the sporty point of view, it is to be notified that the presence of a large shinogi or niku are characteristic of forge schools, or periods of the Japanese history. Sizeable shinogis were characteristic of the Yamato style, and of the associated schools (Uda, Mihara, Nio, Kongobei, Naminohira). Some blacksmiths are also known to have forged their blades with large shinogis. The Osafune (mid-Kamakura period), Kozori, and Ichimonji schools generally forged their blades with a thin shinogi. Sizeable niku were very popular during the mid-Kamakura period. These niku have diminished in thickness during the Nanbokucho period.

The structures (Tsurikomi)

Hira-zukuri

This type of structure does not have a shinogi or yokote (see the first two photographs of the article). Today the shinogis or yokote are edges almost systematically present on modern sabers.

The hira-zukuri appeared especially during the Tachi period. The tanto and ko wakizashi forged at the end of the Heian period (around 806) were often with this structure (a ko- katana or ko-wakizashi is a "in-between" version, with a blade shorter than for a usual katana or wakizashi). Generally, when we are over 35 cm (15") for the nagasa (length of the blade without curvature), this kind of development does not exist. It is undoubtedly the oldest design, therefore reserved for short blades. However, a few long blades dating between 1350 and 1550 have been found having this structure, as to imitate the style of the old sabers.

The hira-zukuri appeared especially during the Tachi period. The tanto and ko wakizashi forged at the end of the Heian period (around 806) were often with this structure (a ko- katana or ko-wakizashi is a "in-between" version, with a blade shorter than for a usual katana or wakizashi). Generally, when we are over 35 cm (15") for the nagasa (length of the blade without curvature), this kind of development does not exist. It is undoubtedly the oldest design, therefore reserved for short blades. However, a few long blades dating between 1350 and 1550 have been found having this structure, as to imitate the style of the old sabers.

A nihonto in Hira-zukuri

Kiriha-zukuri

This scheme shows a lori-mune (triangle shape of the back of a blade) but many Hira-zukuri were Kaku-mune (flat back), older shape of mune.

version with yokote

version without yokote

Nihonto in Kiriha-zukuri of the Heian period (794-1099)

Katakiriha-zukuri

This very particular shape has two different sides. One in Hira-zukuri or Shinogi-zukuri (less common) or Shobu zukuri and the other in Kiriha-zukuri. This type of structure would date from the late Kamakura (1288-1334), and many sabers of this style were forged at the beginning of the Edo period (1596-1643) and later at the end of this same period. Nevertheless some historians believe that this structure would be older, and would have appeared around the Nara period (710-794). Many great blacksmiths have given us blades of this structure. This is the case of Kanemitsu, Sôshû Yukimitsu and Sadamune, Awataguchi Kunitomo, or even more recently during the period of the shin- shinto Gassan Sadakazu, Suishinshi Masahide and Taikei Naotane.

Kiriha-zukuri form for one side, and Hira-zukuri for the other

Kiriha-zukuri shape for one side, and Shinogi-zukuri for the other

Moroha-zukuri

Like a sword and not a saber, this type of structure has two cutting edges. This blade shape is most visible on sabers from the Nara period (710-794) as well as the tantos forged after the mid-Muromachi era (1467). Most of the time these tantos were straight and forged in the province of Bizen. The Kogarasu maru is the most famous sword with this structure, forged by Amakuni Yasutsuna.

Shinogi-zukuri

This structure, also sometimes called hon zukuri, has a shinogi as we know it, i.e. close to the mune (back of the blade) and not to the edge of the blade (hasaki). It is also composed of a yokote (edge delimiting the tip, or kissaki) and of a sori (curvature). This type of katana had appeared after the Heian period, around 987, and is still the most widely represented type of sabers today, for katanas and wakizashis (never for tantos).

Shobu-zukuri meaning "iris leaf"

Shobu-zukuri is a yokote-free variation of shinogi-zukuri. Many tantos and wakizashis from the Muromachi period were forged with this structure.

We can clearly see on this image the absence of yokote (transverse edge delimiting the point)

Kissaki-moroha-zukuri

As you might have guessed, this structure has a double-edged point, while the rest of the blade consists of a no-sharp back (mune) like most other structures. This gives a blade having a tip (kissaki) very close to the appearance of western swords. This style appeared in the Nara period (708-781). Sometimes Kogarasu-maru-zukuri is evocated, in reference to the katana Kogarasu-maru, treasure of the Heike family (largest military family of the Heian period) which has this structure.

Kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri

The lower part of the blade has the shinogi-zukuri shape (the most common form for modern or training katanas) or more rarely the hira-zukuri shape (without yokote or shinogi, remind). As you get closer to the kissaki, the shinogi-ji becomes thinner (see katana lexicon) and the upper part becomes similar to the shobu-zukuri structure. Many sabers of this style were forged in the early Kamakura period (after 1182) in the Yamato province.

U-no-kubi-zukuri meaning "cormorant neck"

This particular structure is based on the kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri, but near the kissaki, the structure takes again its original shape. As for the kanmuri-otoshi zukuri, it is therefore based on a shinogi zukuri, or more rarely on a hira zukuri.

Osoraku-zukuri meaning "can be"

This type of structure has a very long kissaki, more important than the lower part of the blade. It is a type of kissaki that is very rarely found on some tantos and wakizashis. This structure was created by Shimada Sukemune.

As you can see the kissaki is really long, it is absolutely not comparable to an O-kissaki (very long tip, a common type of kissaki).